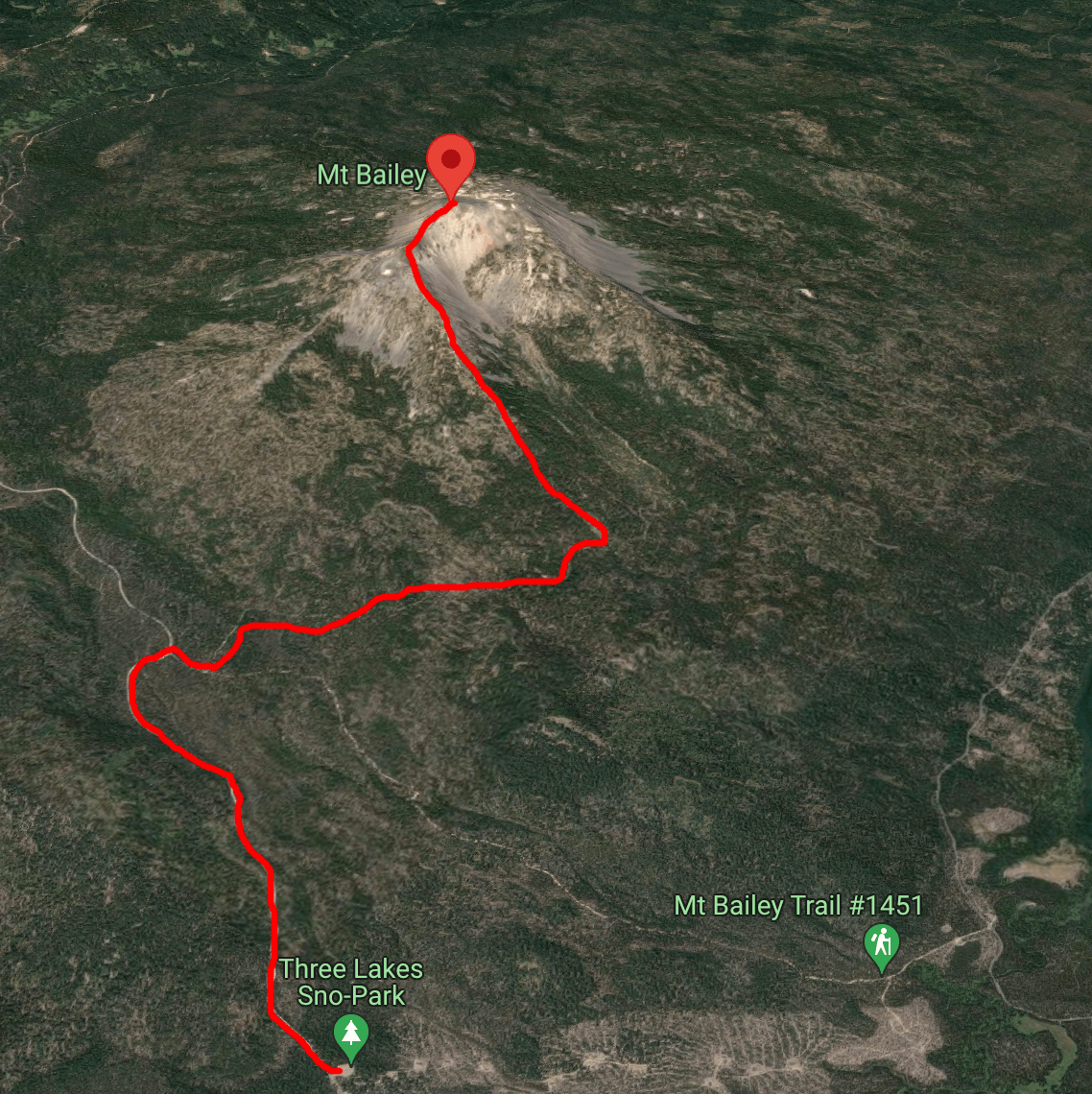

Youxlokes and His-chok-wol-as (Mt Thielsen) are a pair of volcanoes on either side of a serene mountain lake. His-chok-wol-as is an ancient volcano compared Youxlokes and has been almost entirely eroded by glaciers which have long since melted out. What remains at the summit is the magma core itself, acting as a dramatic lightning rod for the central cascades. Youxlokes, on the other side of the lake, is a far younger volcano with an obvious summit crater and the classic dome shape we expect at this point. To summit Bailey you need to ascend +3,000’ over about 6 miles, much of that distance on mellow forest roads and nordic trails.

Storm

The last day I spent at Vesper Meadow it started pouring rain, it never even let up for long enough that I could run outside and get all my gear in the car, so unfortunately everything got a tiny bit damp before the drive up to Crater Lake. Rain at low altitudes (vesper is at 4000’) does mean… snow at higher altitudes! I watched the weather forecast pretty carefully to try to figure out whether there would be enough snow to cover up the ground a bit and making the skiing in/out more fun – there’s a bit of a risk here: in areas with a lot of blowdown a dusting of a few inches of snow on top is more dangerous than no snow, since it just hides all sorts of junk that you can crash into.

My original plan was to climb Scott Peak next to Crater Lake, which I have never actually seen. On one visit to Crater Lake with Allison there was too much snow to see the lake and on our second visit a year or two later a fire was raining ash down on the lake blocking any views with a thick layer of smoke. I had hoped that I could get to Scott Peak on some forest roads from the east side despite the park being closed due to the storm, but the roads were way too muddy for Jacob (our twilight blue outback) to handle. I ran into a friendly pair of locals in a lifted jeep with 4’ tires who took the time to explain that not only was I going to get stuck a half mile up the road but there was a very large downed tree a half mile later. So instead, I turned around and headed north for Diamond Lake and the twin volcanoes that surround it.

I parked at a sno-park at the base of Youxlokes where it dawned on me that it would be, for the next 24 hours at least, actually winter again!

Powder Day

Avalanche Risk

So far on this trip the avalanche risk has been zero because in spring the snow becomes one giant fused together mass, which only melts out on the surface. There is a small risk in springtime of glide avalanches, which happen when water gets between the rock below and the snow, but this is a bigger risk on mountains that have solid rock (especially granite) under the snow. On volcanoes which are basically made of crumbled up lava this is usually not something that can happen.

What was I thinking about on the way up? There were three distinct avalanche concerns in the forecast: (1) the heavy storm snow below treeline where the temperatures were higher could connect into slabs and slide, (2) the wind-blown snow above treeline could consolidate into a slab on the leeward side of ridges, these slabs could be as big as 4’ and would be very likely to slide, and (3) the dry snow above treeline could slide on its own on steep cliffs.

The ascent route stays on a ridge with no exposure to avalanche terrain at all. As we got closer to treeline I started looking for possible signs of whether the descent we wanted to do, which is very exposed to avalanche terrain, would be safe.

A few minutes after taking that video I found a fumarole. Evidence that Youxlokes is still an active volcano!

The route here curled around onto the southwest face where the wind had pummeled the mountain during the storm and the avalanche conditions here were very distinct from what I saw on the south/southeast faces. Instead of a big slab sitting on top of ice, it now felt like a very small slab that was well attached to the ice underneath.

You might be wondering how all this avalanche information actually gets used to make decisions. Before the trip I used a mapping tool to identify potentially dangerous ski terrain, which is anything between 30 and 40 degrees. If the avalanche forecast that the professionals publish every night says that this terrain will be dangerous, then I just block it off on the map – so no matter what I find out in the mountains the next day I will not ski there. But that doesn’t mean I can’t ski below that terrain, this depends on how extreme the avalanche risk and in particular whether or not natural avalanches might happen (distinct from human-triggered avalanches). So today my goal was to evaluate whether natural avalanches were likely and whether I should retrace my steps to descend, or if that big east bowl was safe to ski. A second consideration was that the folks I met had not closed those steeper lines for skiing, so we also ended up digging a small pit near the summit on terrain similar to the steep lines to evaluate whether wind slabs existed (which they did) and to convince ourselves that the forecast was right and that this terrain was too dangerous.

A short traverse across the southwest face took us past the lower crater, I’m actually not quite sure if there is a higher crater on Bailey or how they mountain was built up above that point.

On the upper ridge Nathan, Emily, and Mike caught up with me as I tried to decide how to tackle the final ridgeline. Eventually, we settled on staying right on the ridgeline itself which involved a short exposed traverse and then some scrambling over rocks. Along the way we found some very cool features, like this rock hole which, if you were to step through it, would dump you off the side of a hundred foot cliff and onto the ski slopes below!

It took a half hour or so to get through the ridge and onto the final summit plateau, where I had lunch while I waited for the others to catch up. We had agreed that I would go first, check it out, and then text them if it felt safe. It’s always a little tricky to navigate teaming up with strangers since you don’t want to push them outside their comfort zone. Nathan suggested that I should have brought waivers for them to sign.

We dug a final avalanche pit to evaluate conditions and as expected we found a dramatic 2-4’ wind slab which was not well connected to the old snow underneath. It’s almost certain that we would have set of a human-triggered avalanche in that terrain. I repeated the test we did in a simplified manner for this video (the proper test involves tapping the column of snow with increasing force to see how well-attached the two layers of snow are).

And then we started skiing down!

After a lot of traversing through the woods we got back to the cabin where the three friends were staying for the night. Not only had they broken trail for hours the night before but they carried in enough beer and wine for a small army. I drank a few bottles with them, just to help them not have to carry it all back out on the way back to the car. Before the sun set fully and before the fire in the cabin got warm enough to make it hard to go back outside I headed back to the trails to make the final trek home.

Eventually, I hit the fire road and was able to sort of half-ski and half-push myself back to the trailhead.

After that, I switched trailheads to the His-chok-wol-as (Thielsen) trailhead and capture a nice photo on the drive over.

And here’s the footwear update. When it’s really cold out I wear down booties!