Mt Shasta stands alone at the north end of California, a formidable mountain without anything comparable nearby. By prominence and isolation Shasta is second only to Mt Rainier in the continental US rising over 10,000’ above its plateau and with the next mountain of similar height being in the Sierras three hundred miles to the south. Even more remarkable is that Shastina, the older volcanic peak connected to the main mountain, is over 12,000’ tall making it comparable in size to Lassen! Unfortunately, this year was an exceptionally low snow year and Shastina is almost snow free already at the end of March.

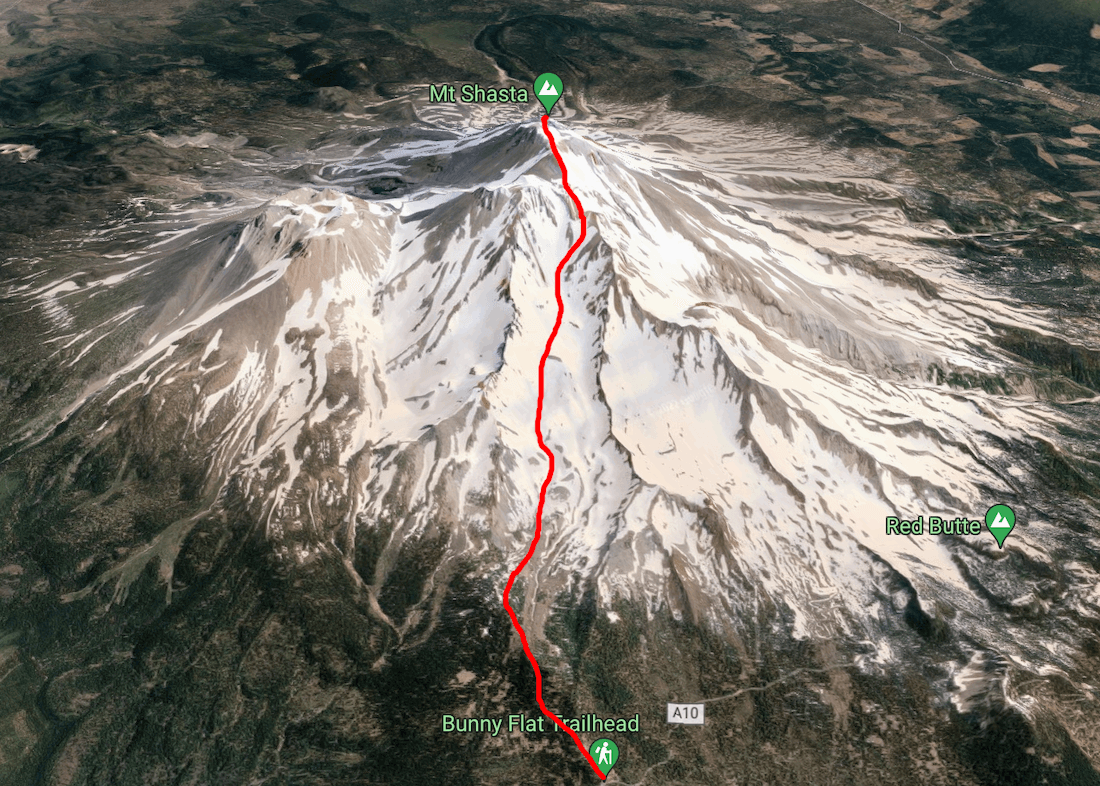

Shasta is built from four major volcanic cones, the Hotlum cone is currently the tallest, formed 8,000 years ago, and is still active with obvious fumaroles venting sulfur onto the summit plateau. Just to the south is Misery hill, a remnant of one of the earlier volcanic eruptions. Misery hill forms a false summit, blocking views of the true summit and is often the end of the road for many ascentionists. Getting to the summit of the Hotlum cone by the easiest route, Avalanche Gulch, involves +7300’ of elevation gain to the peak at 14,179’ over about 5.75 miles and is often done in two days with an overnight at Horse Camp (at 8000) or Helen’s Lake (at 10,600).

Driving North

Step one to getting back to Shasta was turning around and driving eleven hours north from Vegas where I had been rock climbing for the last week and a half. This was extra hard because I unexpectedly got to spend three days with the COE staff during red rocks staff week and I really didn’t want to leave (and given the snow level in Oregon, maybe I should have kept climbing? The FOMO is real).

In the image Shasta is the somewhat hard to see shadow at the center of the image, behind the range of closer mountains.

Eleven hours is a long… long… long… time. I called Allison on the drive, Jimmy tried to call me, I listened to the Arcane soundtrack twice, made some progress on the audiobook I’m listening to, and for a few long stretches I just drove in silence. Every once in a while Shasta would pop back into view, a bit bigger and a bit more imposing!

Day 1: Bunny Flats to Horse Camp

One really nice thing about Shasta is that there are very few restrictions. You can camp in your vehicle at the trailhead, which should be allowed everywhere. So I spent the night in the car with a beautiful view. If it isn’t obvious by now I find sleeping in the car very comforting, I think because of how much time Allison and I have spent living out of the car on trips. I particularly like it when it rains, which it did not do while I was at the trailhead and is also the main negative of skiing Shasta this year–there hasn’t been real precipitation since January, part of the extended drought that continues to cause issues for California.

It’s probably not obvious in video but I’m wearing flip flops. Optimal footwear for early morning hiking when the temperatures drop below freezing at night. I’m a firm believer in not putting feet into shoes unless necessary which so far on this trip has led to one bloody middle toe (bashed on a salt pillar in badwater basin) and one bad flapper on my big toe (slipped descending barefoot in red rocks). COE has their students wear shoes for a reason.

Cool fun thing about overnight freezes, you get hoar frost! These are crystal formations that “grow” out of wet ground when the temperature is right. I also snapped a picture of some signs on the hike out which I think are supposed to be readable in a high snow year?

Day 2: Summit Day

Before this next video it’s worth saying that I get lonely pretty fast in the outdoors. I know plenty of people who can go weeks by themselves (usually hiking) but almost all of my outdoor experiences have been in sports that for safety reasons require more than one person. It’s also just more fun to be with friends! I tried for this trip to wrangle everybody I know on the west coast into coming to ski some of these mountains but unfortunately limited vacation time and/or lack of snow led to pretty much everybody bailing, which I found out while sitting around Horse Camp where I had service. Dear skiing friends: I really wish I could have done these mountains with you, I hope we can do them together in the future!

Anyway, once I get past the inertia of being by myself and start moving, things usually fall into place. The avalanche risk was non-existent on Shasta which made me feel much more comfortable about being up there alone.

Notice anything funny about the look of these little hills and valleys? These are moraines! There are no glaciers on the south side, but it’s evident from this geology that there were glaciers at some point in the past few thousand years which pushed the rocks down and to the side to form these valleys. Until about ten years ago the glaciers on the north side of Shasta were growing, although with the recent major droughts I doubt that is still true.

At this point I recorded a video about pooping in the mountains, but I guess it was windy and I didn’t notice? So you can’t really hear me. Basically what I said was: about 10,000 people try to climb Shasta each year and unlike in Canada or Europe where they just put pit toilets all over the mountains and then helicopter the waste out, in the US we’ve really leaned into this idea of wilderness with no helicopters flying around. So everybody brings a wag bag up with them on the mountain, which is usually two or three plastic bags and a bunch of sawdust or kitty litter, and then you carry it all back out on the way down. This is a decent system, but the views of the mountains from the Canadian high-altitude bathrooms can’t be beat, so I think their system is also pretty good.

Despite Shasta being a comparable climb to the Mt Whitney (6000’ in a day over about 5 miles) I was moving much faster, in just two hours I gained almost half the elevation and was standing at the base of the Heart, one of the identifiable features along the Avalanche Gulch route.

And a half hour later I was near the top, where I had to cross through the Red Banks.

After the Red Banks you traverse a ridge for about a half mile until you pop out at the base of Misery Hill, which would have been the summit of Shasta if not for the most recent volcano eruption.

You can’t hear me at the end, but what I tried to say was something like “The reason they call it Misery Hill is because the true summit is way over there”. A huge percentage of the people who attempt Shasta each year turn around at the top of Misery hill– the summit is actually only 300 feet higher but it’s about a half mile away and at 13,800’ it’s a long way away in terms of effort.

With a bit more effort I was on the summit, relaxing with Matt from Colorado who made me really wish I had brought my own can of pringles.

I had to stop and lie down every 500 vertical feet or so, my legs were wrecked from the climb up combined with the altitude. On the bright side, I had absolutely no issues with altitude on Shasta, a clear sign that either exhaustion plays a big part in the headaches that I often get or that the acclimatization from Whitney didn’t go away even after a ten day break.

I spent a tedious thirty minutes at this point running back up a hill to my campsite, gathering all my gear, and then running back down to my skis. I had considered doing this step in the morning since I was start late anyway but it’s always a little tricky to find stashed gear on a mountain when you come back later. After that I skied out, jumped in the car, and drove to Ashland, Oregon to crash at our friend Jeanine’s place in the mountains there.