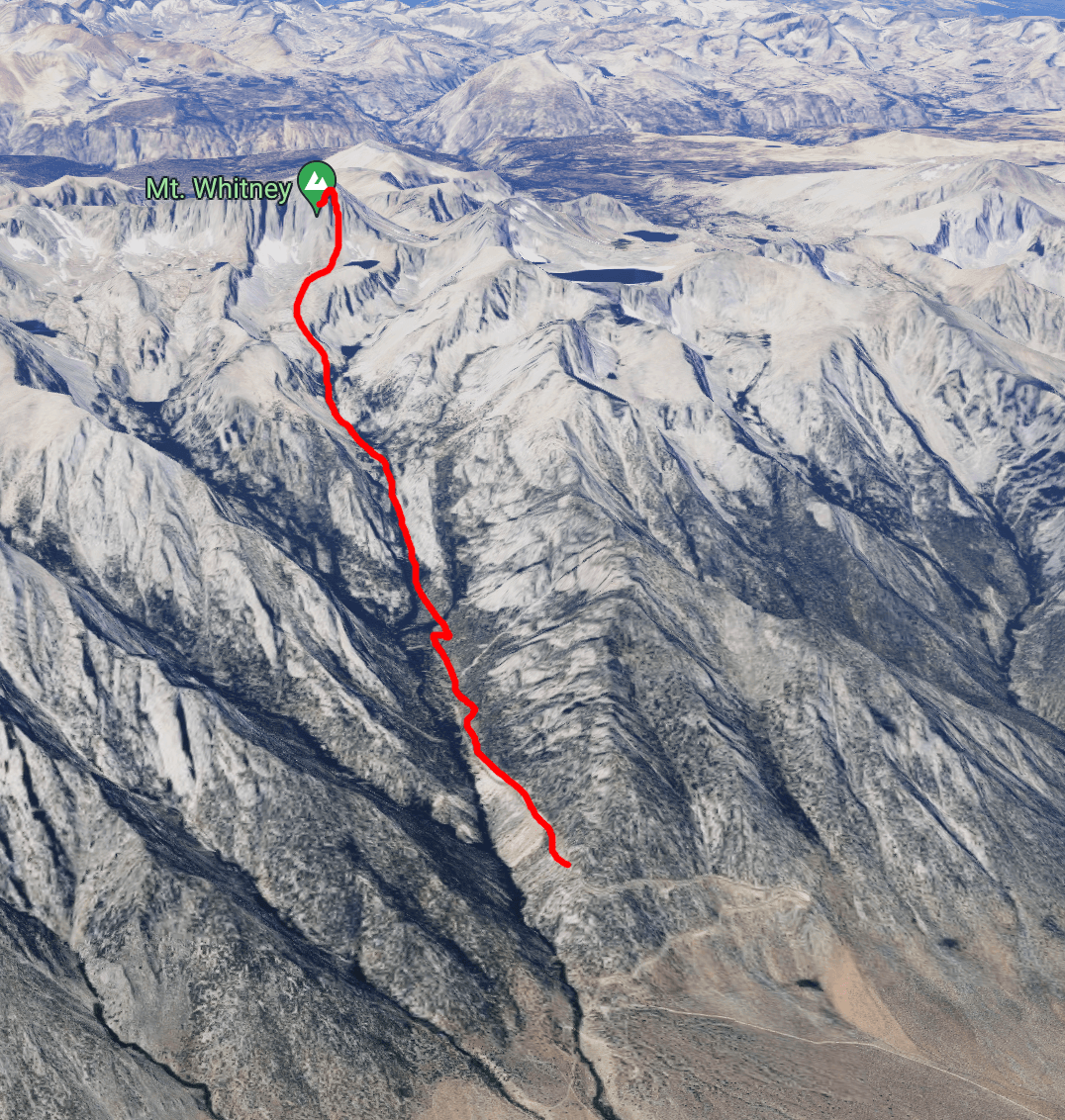

What stands out most about Mt Whitney is the abrupt sheerness of the east facing cliffs. The whole eastern flank of the Sierras is like a wall, a byproduct of the way the uplift zone is tilting the Sierras up and out of the Owens Rivery Valley. The granite and relatively young age of the mountains also makes for impressively steep valley walls and canyons. Our car was parked at the high gate of the Whitney Portal road, about two miles short of the official trailhead. So our plan for day 4 was to wake up with the sunrise and move our camp up to the trailhead proper on foot and then start early on day 5 around 2am up the Mountaineer’s Route. In total we were looking at about 1000’ more elevation gain over 2 miles on the first day and then an astounding 6000’ of elevation gain over just 4.5 miles to gain the summit and finish the Low to High! It would be ridiculous at this point not to say that we were nervous, but our overall energy levels remained good and our spirits were as yet unbroken.

Trailhead Relaxation

The two mile walk up to the trailhead was strenuous with our fully loaded packs but also just a nice stroll through the woods. One of the perks of the Whitney Portal area is that the cliffs surrounding you are magnificent and it’s easy to spend long minutes staring off at nothing in particular. Or right at Mt Whitney as it looms over you just a few miles away! The scale of things felt very out of proportion after being in Death Valley, where huge distances can look quite small. In the Whitney area there are a lot more trees and rocks to use to judge scale and I find that my estimates of distances are much more accurate.

We set up our campsite behind a little rock near some streams to avoid the noise from a group of twenty or so middle schoolers who were up on some sort of mountaineering trip. Pretty awesome middle school! After setting up, we spent a few hours in the sun and eventually in the shade relaxing, reading books which we had left behind in the car, and generally trying not to think about the enormous effort we would need to generate the next morning.

Mt Whitney

We started walking at about 3:30am or so after a quick warm ramen breakfast and luckily just barely caught the full moon setting behind Mt Whitney. After that we were in the darkness hiking up the short 1 mile section of trail from the trailhead to the break off to head up the north fork of lone pine creek, which leads you past three lakes (Lower and Upper Boyscout lakes and Iceberg Lake) to the base of the Mountaineer’s Route. Nothing too exciting happened until about 7am when the sun came up and in a moment of fantastic alpine drama revealed the Inyo Range and the upper snowfields of Whitney all in one swoop.

We arrived at Upper Boyscout lake, the halfway point of the route, right as the sun crested the mountains and we started finally seeing our shadows, somewhere around 7:15am or so. Although the lakes are all frozen over and temperatures had been quite cold for the last month the snow level was very low for this time of year. The Sierras, and most of California, are as usual now in a pretty intense drought. Unfortunately, the snowpack in the Sierras feeds a lot of the local towns and eventually Los Angeles and San Francisco through their runoff– so a lack of water here has an impact all over the state.

Upper Boyscout lake is also the 11,000’ height, which is around the same height as Telescope peak and also the height at which I almost always start getting an altitude headache. Most people experience two common symptoms of altitude sickness: headache, which is a sign of HACE or brain swelling, or a shortness of breath and cough, which is a sign of HAPE or liquid slowly filling your lungs. In practice, neither pose a huge risk if you plan to go up at a reasonable clip and then turn around and go back down. Most people feel recovered within a few hours after descending. If you plan to stay at altitude though you have to be much more careful and only ascend a small amount of elevation each day to allow your body to adjust its physiology to deal with the reduced availability of oxygen. In short: I started getting a headache.

It’s entirely possible that my inability to do basic math is altitude related as well. Conclusive testing will have to be performed on other mountains.

Iceberg Lake at 12,600’ is way up there and we were definitely feeling the altitude by now. Our pace was starting to sink below our expected time but we were also still well on track to make it to the summit in a reasonable amount of time. The snow conditions were about as good as they could have been: snow that was solid enough to stand in but not so solid that you couldn’t kick your boots in deep enough to get a firm footing.

At the top of the mountaineer’s gully we popped out at a small col that separates Mt Whitney from the ridge to the north. There are two options from here: climb relatively solid 4th class straight up to the summit or traverse far to the west and then back on much easier terrain. We chose to do the traverse since neither of us felt very comfortable in exposed rock climbing terrain in ski and mountaineering boots, respectively.

And that was that. Low to high, complete. Big dream, finished! It was a bit of a special moment for both of us because a lot of the big trips we’ve planned in the last few years haven’t gone well. Alan attempted the PCT and the Arizona trail and got stymied by smoke and getting sick, respectively. I also have had a few exciting trips not pan out over the last few years and got a bit burned out on planning these kinds of epic adventures. So to have spent so much time agonizing over the logistics and to train for months and have it pay off was a confirmation that we can still do this and that we can have fun doing it!

We soaked in the moment for a bit, it’s possible some eyes got watery, and then we listened to the sound of our heads pounding and started heading back down as fast as we could move in a safe manner.

Back at Iceberg lake an hour or so later we were really really feeling it.

We both took an ibuprofen, which is a relatively safe thing to do once you’re descending and out of dangerous terrain. Not a smart move on the ascent, since it will mask some of the symptoms of altitude sickness but it doesn’t treat any of the underlying cause – allowing you to push into terrain and altitudes that might be debilitating when the drugs wear off.

I felt a little guilty at this point because I had carried my skis up, which allowed me to zoom away back down to a lower altitude at upper boyscout lake where there was also running water to re-fill my bottles.

Pretty quickly we got back down to lower boyscout where the conditions got a little tougher. The snow wasn’t really skiable anymore with all the exposed rocks and plants but the snow was also super soft from warming up all day. Those conditions mean you have to be careful not to punch through and get your leg stuck as you’re moving forward, or you can twist your hip or knee pretty badly.

That all went by pretty fast though and by late afternoon we were back at our campsite. We cleaned things up and then hopped on our bikes to get back to the car!

There wasn’t really any reason to stop at the car either, we had bike all the way up from Lone Pine and it would have been a waste to stop there and drive down. So I took the first run and biked back down the hairpin to the lower pine campground and then Alan took a turn biking the final five miles back into Lone Pine.

And that was it! We had a celebratory beer in town and then drove over to Panamint valley for some well-deserved rest. On day 6 we organized our gear and picked Alan’s car back up from Death Valley, before driving on to Vegas for some rock climbing with friends.

Thanks for tuning in to this one!