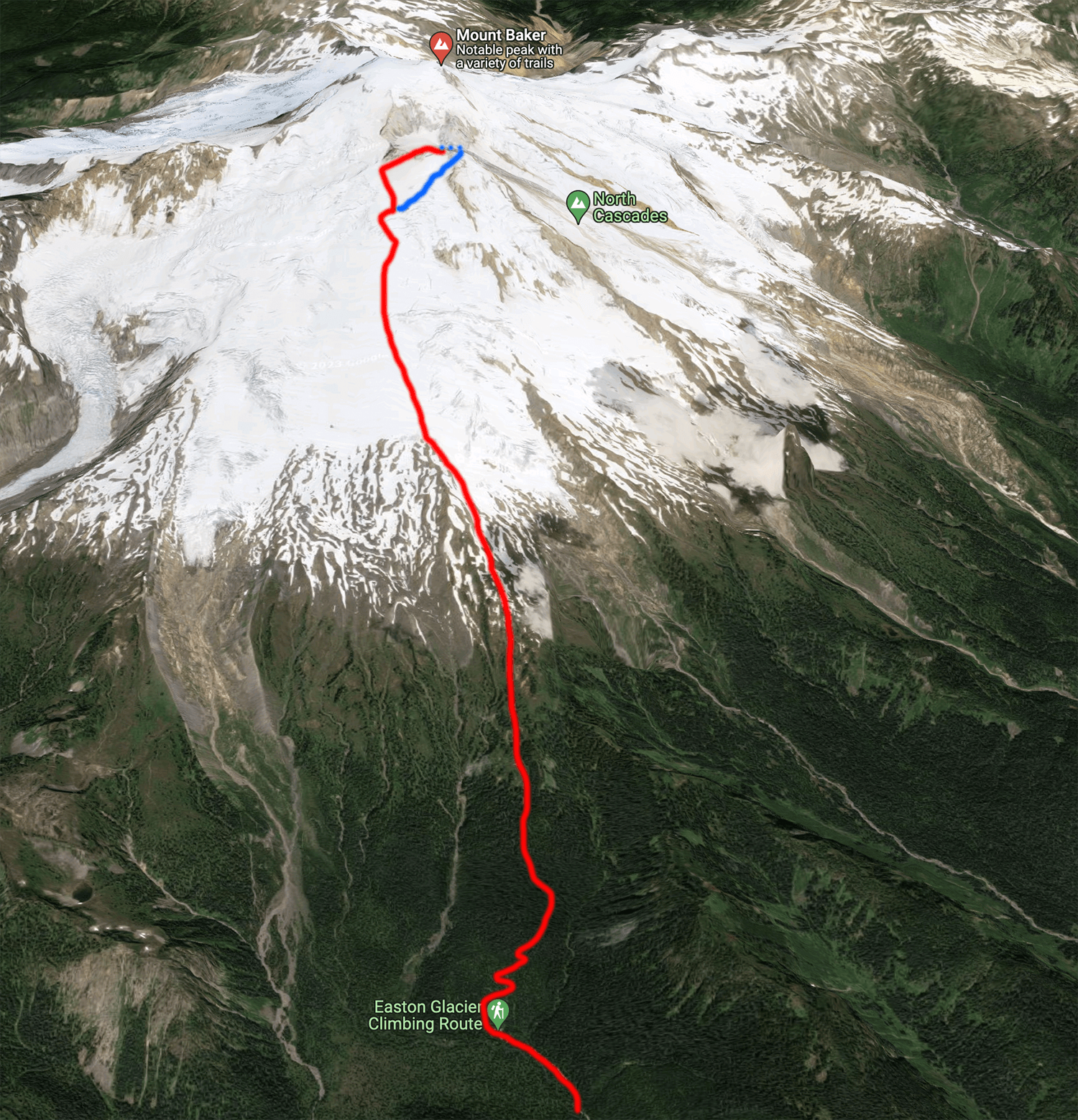

The huge steaming crater on Koma Kulshan is flanked by two major peaks and a few minor ones, Grant on the northwest corner is the main summit at 10,871’ while Sherman on the southeast corner is its little sibling at 10,165’. Unlike the main summit, Sherman is a small mud pinnacle with steep slopes on all sides. Getting to Sherman Peak via the Squak Glacier is an ascent of about 7000’ over a little more than 5 miles.

Shay just finished his last full semester as a graduate student, so to celebrate a bit he flew in on a Saturday afternoon and we made a plan to climb two volcanoes in three days so that Shay could fly back the next Wednesday. Unfortunately, a cold front blew in unexpectedly bringing temperatures down below freezing on the summit of Rainier so we crossed that off the list. Then, Shay’s first flight was delayed and he missed his second flight, so he didn’t make it in to Seattle until 11PM on Saturday night. I picked him up from the airport, we drove home, and slept for two and a half hours before starting the drive to Koma Kulshan!

We timed our trip pretty well, the road was snowed out about .7 miles from the trailhead, but the trail itself was almost entirely snow covered. We were able to put skis on and skin from the trailhead up into the forest along a beautiful trail up through the trees. On the way out this trail turned out to be a super fun (and fast!) descent that got us back to the car in no time at all. 90 minutes out from the car we popped up out of the woods into open meadows.

The upper mountain was socked in a cloud layer, but we were still enjoying fantastic views east into the North Cascades looking at Shuksan to the northeast, Baker Lake directly east of us, and many enticing granite peaks farther out into the national park. Around this time Vivienne (sp?) a friend of Allison’s and Ilia (?) popped out of the woods behind us and we spent most of the rest of the day leap-frogging each other and chatting up the mountain.

If you’re curious, we usually take a break every 45 to 60 minutes on these ascents. Depending on temperature and energy levels, every other break might be a longer sit-down break while the others we just snack and stand around. It’s tempting on a mountain like this to push farther and take fewer breaks, especially earlier on in the day, but my experience is that at our training level this always backfires and you end up bonking an hour or two later. 45 minutes for me is about ideal for refueling. Bonking is when your body falls so far behind on the fat to sugar conversion compared to your energy expenditure that your body just shuts down, I don’t bonk often since I’m pretty careful about taking breaks, but when I do my pace drops by 50% or more and it can take a serious 30+ minute break to recover enough to go on. At each of the breaks I take, I usually try to eat somewhere between 250-500 calories and drink a cup or two of water. Often in a full ascent I’ll consume 2-3000 calories and 2-3 liters of water total. I don’t track my stats usually, but a rough estimate is that a 5000’ 5 mile hike burns around 3000 calories on the ascent and takes about 5 hours so we’ll almost always be losing some energy overall. Altitude throws a small hitch into this, low oxygen at higher altitudes slows digestion and often makes me lose my appetite for high sugar foods. When un-acclimatized I also get a consistent altitude headache that starts between 8 and 10k that makes me less likely to eat replacement-level calories. So basically, most people who do one-day mountain climbs will run a fairly significant caloric deficit while ascending and then make that up with a burger on the way home!

Around 9000’ at 10am we finally popped into the cloud layer that was obscuring Baker’s summit. Temperatures dropped pretty substantially here and navigation got a tiny bit more complex! At this point we split off from the main pack of skiers and hikers who were headed to Grant, the main peak on Baker, and we instead circled around the south rim of the crater to start the ridgeline ascent to Sherman peak.

We don’t recommend Sherman Peak if it isn’t covered in snow! It’s a chossy mudpile that is terrible to walk up and a little dangerous. We moved slowly up the ridgeline and by the time we got to the summit proper the cloud layer had blown off and we were in full sun, it was HOT, and the snow immediately started turning to slush. We had some snacks and enjoyed the warmth, probably for a little too long, while we debated our exit strategies. The problem as, I mention in the video is the massive bergschrund crevasse lurking at the bottom of the south side slopes. With the warming temperatures a wet loose avalanche could easily pull us into there and risk a 50 or 100 foot fall onto ice, definitely not worth the risk. Instead, we chose to ski off the north side of the peak and then contour around, avoiding the slopes that were exposed to the bergschrund and allowing us to escape past it on the side and get back to our original ascent path. This worked pretty well, but as you’ll see in the videos we set off a LOT of small wet loose avalanches.

Our tactic here was to ski slowly across the slope to try to set off avalanches below us, and then to wait those out as they cleared out the dangerous top layer of snow. We did discuss the risk that a wet loose slide might start above us and sweep us down and that we should just reverse our ascent path which didn’t have any of these risks, but we weren’t seeing the signs associated with natural wet loose avalanches (roller balls) so we felt that the warming hadn’t hit that point yet. The slides might not look too dramatic, but we were mostly concerned with the risk of being swept into a crevasse not the possibility of being buried.

After that we had an extremely enjoyable ski out on huge snowfields, doing a little bit of crevasse dodging before we got back to the car around 2:15pm! Back to Seattle for a shower and then we went straight to dinner with friends.